The poster was outraged about the the book and its focus on the Waffen-SS, specifically the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, without any mention of atrocities carried out by this force, especially the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre.

This is an excellent point, and it raises important questions both for this specific case, and dealing with atrocities in military history and gaming generally.

War gaming involves recreating events of great suffering and bloodshed as entertainment. It is understandable that some people would be offended by that. Not simply pacifists, but veterans as well. Would you want to play out a war gaming scenario depicting a battle in which you fought, when your friends and buddies died in that fight?

The answer for some is yes. In fact, I've personally helped run a refight of a Vietnam War engagement in which the commander of the American forces came to the game and participated in a question and answer session with the players afterwards. Of course, this game was at a small convention held in a museum and it was very much billed as an educational event. For others, quite understandably, the answer is no. It brings up too many memories. Of course nearly all gamers respect such boundaries amongst their fellow players.

A standard defense of historical war gaming is that it is educational. In fact, the leading miniature war game national society, the Historical Miniatures Gaming Society (HMGS), is a "non-profit, charitable and educational 501(c)3 organization whose purpose is to promote the study of military history through the art of tabletop miniature wargaming." (see here)

But that defense undermines the most common response I get whenever I bring up ethics and war gaming, questioning the depiction of groups like the SS in war games. "It's just a game, lighten up!" Just a game is never a reason to ignore such concerns, because historical war gaming is educational, as all games are. War gamers, and especially game companies, have a moral obligation to address these questions.

The other common response is to retreat into Moral Relativism or the Whataboutism fallacy, claiming that applying moral standards to conduct in war is wrong, or that all military forces have historically committed atrocities so we should not single out groups like the SS. Moral relativism only works for those who subscribe to that philosophy, or those who somehow believe armed conflict has a different morality then peacetime. In that case, there is no shared common ground and further discussion is of little value. And, of course, the 'whataboutism fallacy' has the word fallacy right there in the title; "everybody else is doing it" has never been a valid defense of any action one might take.

The other defense revolves around "fun." Essentially, those who bring these issues up are no fun, indeed joy killers. Why can't we just let them have harmless fun with toy soldiers?

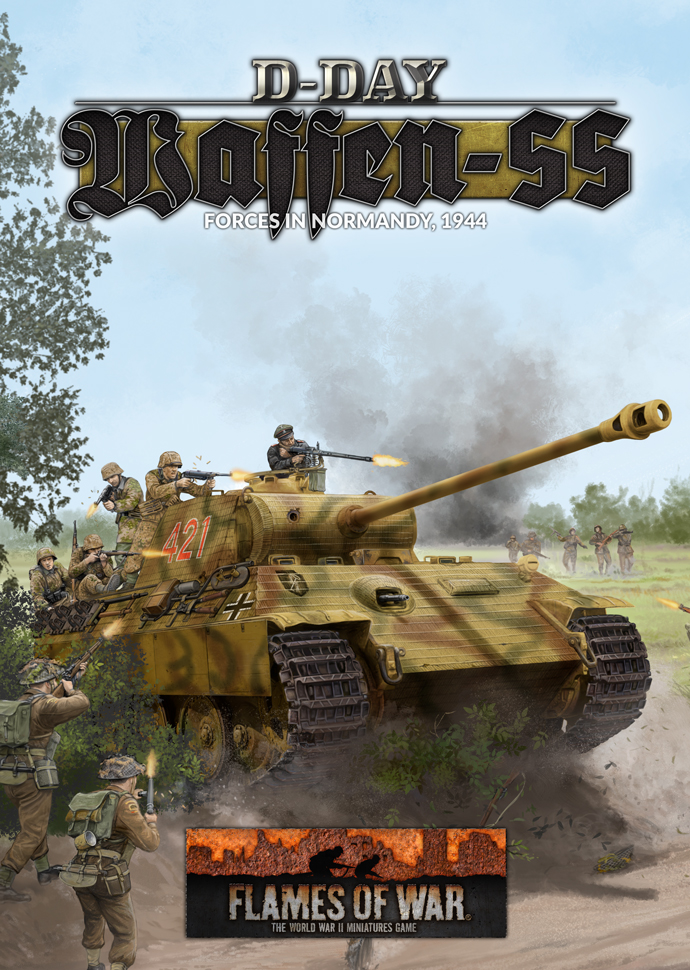

Why not? What harm does this book do? Mitch Reed's review of the book is here, on the No Dice, No Glory website. He doesn't mention any harm. In fact, his review doesn't mention anything about the atrocities at all. It's just an excited discussion of how 'cool' this unit is, discussing them exactly as a Warhammer 40K site might discuss a new unit of Space Marines. The "unique flavor of the SS is represented by a few distinct differences" from the standard German lists, but apparently that unique flavor is limited to uniforms and equipment, along with a few special rules mentioned in the text. The atrocities and abhorrent ideology of the Waffen-SS is not mentioned or described at all. The book removes the historical context, reducing them to a "cool" unit for war gaming that has a "unique flavor."

Of course, other genres of games also deal with this problem to a greater or lesser extent. In 1997 a roleplaying game company, White Wolf Publishing, published Charnel Houses of Europe: The Shoah, a setting for Wraith: the Oblivion incorporating the Holocaust. The work handled the subject in a sober and mature manner. It produced a setting that may have never been used in a RPG campaign, as it was exactly as depressing as one would expect, but it brought a more thorough understanding of the Holocaust to an audience that otherwise might have ignored the event. A copy of the work is kept in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museums collections.

In contrast, the video game industry even today fails miserably with these topics. All too often groups like the Waffen-SS are reduced to "bad-ass" 'skins' and collectible uniforms and equipment in first person shooter MMOs which barely nod in the direction of historical accuracy. The audience only seems interested in historical accuracy when it can be used as a weapon to keep 'skins' depicting people of color or women out of their game play. This article about video games which white wash German crimes highlights the issue, and points out that video games are decades behind historical scholarship on this subject - the same thing can be said for miniature war gaming, though must miniature war gamers would consider themselves more historically knowledgeable then their videogame playing counterparts.

Flames of War, of course, glorifies the SS as a fighting organization. I can't think of a WWII rule set that doesn't to at least some extent. Just as bad, they all play down or ignore the atrocities and ideology.

The answer is not stop war gaming, nor is it to stop war gaming the SS. Historical war gaming is, after all, historical, and refighting such battles is an integral part of the hobby. Moreover, someone has to play "the bad guys." You can't refight Arnhem, for example, without some SS troops.

At the same time, we have a responsibility to educate that cannot be ignored. War game rules should mention SS atrocity, and acknowledge their crimes. Equally importantly, they should resist the urge to assign them enhanced statistics, this treats the SS as if their superman delusions were real and is a disservice to humanity.

I understand the desire to separate war gaming from the messy real world, to try and avoid anything that smacks of politics. It won't work, though, and it is harmful to our hobby. As this article on former SS members still proud of their service makes clear, the veterans of the organization for the most part have rejected responsibility. Attempts to white-wash the history of the Wehrmacht and the SS are constant, as this article about a historian threatened with prosecution for writing the truth shows.

The sad fact is, our hobby is a prime recruiting ground for racists and right wing fanatics, who can easily "hide in plain sight" in the hobby, recruiting new members and spreading their historical disinformation. When companies like Battlefront put profits over morality and ignore or white-wash the crimes of the past, then intentionally or not they are supporting such movements.

We have a moral obligation as war gamers to ensure that such white-washing does not occur in the games we run. We have an ethical obligation to consider these questions and how our games relate to them. Even if that makes them "less fun." That doesn't mean every game must be focused on these events, but we need to acknowledge them, and especially game books should mention them placing the units described in a full historical context rather then simply using them as cool "options" for players. Works on Vietnam should acknowledge My Lai as well as the mass murders the Viet Cong committed in Hue, for example. Campaign rules for the Battle of Gettysburg should acknowledge that Lee ordered every African-American his army could seize shipped south into slavery. It isn't difficult, acknowledging these crimes. It's simply the right thing to do.

Certainly the history of warfare is complicated and nuanced. But if we cannot at least talk about the Waffen-SS and their atrocities, which are not in doubt... well, then we should give up all pretense of playing historical games at all.

For Further Reading

The following works I recommend for further reading about the 2nd SS Panzer Division and the Waffen-SS. This is not a complete list, obviously.

Adrian Gilbert, Waffen-SS: Hitler’s Army at War

Max Hastings, Das Reich: The March of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Through France, June 1944

Bernd Wegner, The Waffen-SS

Jochen Boehler and Robert Gerwarth, The Waffen-SS: A European History

All views in this blog are my own and represent the views of no other person, organization, or institution.