A version of this article appeared in Knights of the Dinner Table #195 (September, 2013).

One of my greatest joys as a reader is discovering a good book that I have not read before. When it is an old book, an antique book, which I have not only not read but not even heard of, this joy is much greater. Back in 2013, I found that joy while searching for books about witches when I discovered The Lancashire Witches: A Romance of Pendle Forest (1848), a novel written by William Harrison Ainsworth.

Ainsworth was trained as a lawyer in London, but never pursued the profession, instead entering into publishing with his first novel, Rookwood, in 1839. His work was popular, and he was extremely prolific; taking English history as his source he went on to write forty or so historical novels covering centuries of English history. He was a friend and contemporary of Charles Dickens, as well as popular writer whose works sold very well, but his novels have generally not stood the test of time well and he is often forgotten by all but literary historians these days.

The Lancashire Witches, first published in serial form in 1848, is Ainsworth’s best known novel and the

|

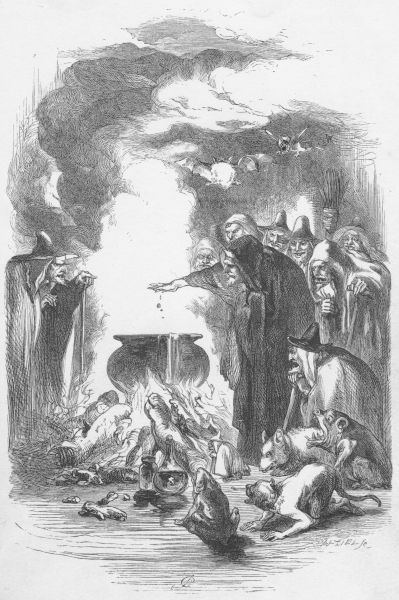

| "The Incantation." Illustration by John Gilbert. |

one which has remained in print the longest. It is a fascinating work which tells a fantastical version of the historical trial of the Pendle Witches. Ainsworth begins the tale with a Catholic uprising against Henry the VIII a couple generations before the Pendle Witch trials, using a conflicted bishop and a fallen priest as a fascinating back drop to the tale, encompassing a quite long introduction. The plot of the novel proper is then contained in three books. Ainsworth builds his plot around a historical account of the trials, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster by Thomas Potts, and makes Thomas Potts himself a wonderfully slimy character in the work. Many of the characters names come from the historical event, but their relationships, roles, characters, and actions are not remotely historical; magic is distinctly real, devils and ghosts make regular appearances.

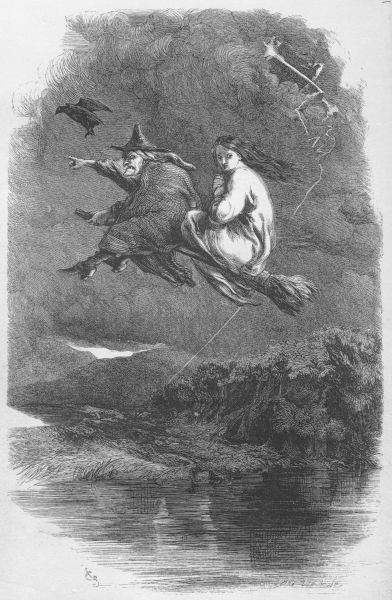

The novel’s protagonists are the tragic lovers, Richard Asheton and Alizon Device. The witches are quite real, and quite devoted to the devil, yet the witch hunters (save the king, James I) are depicted as venal money-grubbers, anxious to accuse others in order to gain benefits. Alizon’s purity is never in doubt, but her unfortunate relationships to witches make her a target of the witch hunters, even as the witches themselves try to sacrifice her to the devil for her purity.

The novel’s presentations of Lancashire country life in the 1600s may not be perfectly historically accurate, but it is quite enjoyable, and anyone who has attended a Renaissance Fair will quickly recognize it as the source of so many tropes of Elizabethan games, it is self-consciously a depiction of “Merry Olde England.”

|

| "The Ride Through the Murky Air." Illustration by John Gilbert. |

For gamers, this book is chock full of excellent examples and characters to steal. All of the various witches can be lifted whole-cloth for use as village healers, villains, or hedge witches in most roleplaying campaigns. Wonderful examples of spells and material components abound, as well as a great example of the internal politics of a witches' coven. Gamemasters can also see the workings of local versus national political leadership when the king visits in the last book of the novel, as well as some excellent plot ideas and concepts for properly using ghosts to push characters along. But the best steal from the novel is Nicholas Asheton, Richard’s cousin and a splendid character that gamemasters can lift whole-cloth and place in their campaigns as a local squire or other minor nobleman. Most of the funniest scenes in the novel center on his exploits.

Ainsworth was a friend of Dickens, but I found myself constantly comparing his work to a French contemporary, Alexandre Dumas. The Three Musketeers depicts the life of impoverished minor gentry in 16th century Paris, The Lancashire Witches does the same for 17th century rural England: both romanticize the time and place, but do so charmingly.

The Lancashire Witches is still in print, you can find several reasonably priced paper editions easily, and it is also available for free from Project Gutenberg and as an audiobook from Librivox. If you ind a printed version, be sure to get one that includes the original illustrations by John Gilbert, they add immensely to the tale and are just plain fun.

If you enjoy a touch of comedy in your melodrama, and some historical spice in your tragedy, or if you just love witches, give this old book a read. It is rather remarkable.

All views in this blog are my own and represent the views of no other person, organization, or institution.