A version of this article appeared in Knights of the Dinner Table #156 (October, 2009).

From 2006 through 2012 I was the "Off the Shelf" columnist for Knights of the Dinner Table, a magazine and comic book devoted to tabletop fantasy role paying games. I reviewed classic andmodern fantasy, horror, and science fiction novels. Every October I tried to review a work of classic horror in honor of Halloween. I am trying to continue that tradition with my blog. You can find previous Halloween Reviews here.

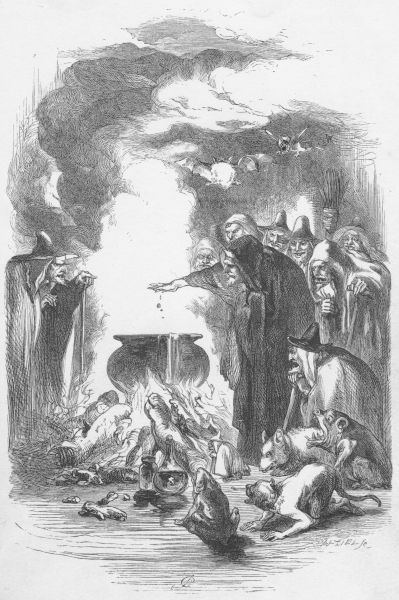

When Halloween again rises from its grave to stalk the cool fall nights, one’s thoughts turn to the classic move monster of yore, that unholy triad of Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Wolfman. The first two first appeared in classic gothic novels of the nineteenth century, widely read and beloved thrillers that often feature in high school reading lists. The werewolf’s historical and mythological roots are deeper than the other two; nearly every culture has some sort of lycanthropic legend. Werewolf tales are particularly widespread in Europe, where true stories of horrific wolf attacks were mythologized into fables such as Red Riding Hood. Despite this rich history, the literary antecedent of the Wolfman is less well known than his two companion classic horrors, in part because that 1933 novel, The Werewolf of Paris, remains under copyright.

The Werewolf of Paris was written by Guy Endore, born Samuel Goldstein. Endore is best known today as a novelist and screen writer who was black-listed as a communist during the Red Scare. Endore was a communist (at least for a time), and was thoroughly immersed in the avant-garde intellectual movements of the 1930s. He was also educated in Europe.

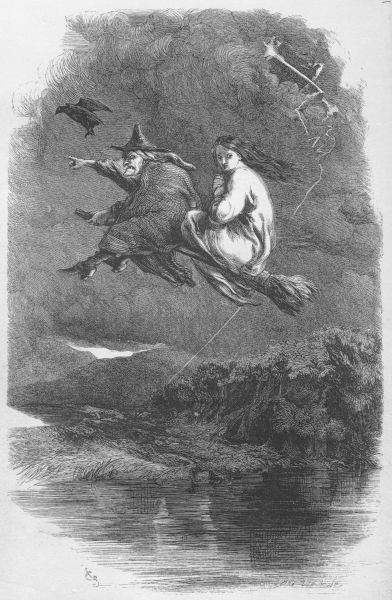

Endore’s political leanings add a great deal to The Werewolf of Paris, a truly remarkable horror novel. Set in nineteenth century France, the novel tells the story of Bertrand Caillet as told primarily by his step-uncle, Aymar. Unlike later versions of the werewolf myth, Bertrand is not cursed by the bite of another werewolf but suffers rather from a family curse. The novel tells the origin of this curse, and then details Bertrand’s sad life from birth to death. The novel climaxes during the Franco-Prussian War, Bertrand is in Paris during the German siege, the Paris Commune, and the eventual retaking of Paris by the Versaillais troops.

The descriptions of the Commune are vivid, and throughout the novel Endore’s Leftist sympathies leak through the text, yet this enhances rather than detracts from the experience, allowing the reader to immerse him or herself in the languid yet fevered atmosphere of France in the nineteenth century. The contrast between Bertrand’s bucolic home village and the beleaguered Paris, were Bertrand’s depredations are truly the least of horrors is particularly acute.

In addition to the politics, Endore’s novel reeks of sex, and the sex is both more blatant and more depraved than the bubbling under-currents of Victorian erotic repression found in Dracula. The werewolf tale has always had a direct connection to sex, again Red Riding Hood is the most obvious example. The Caillet family curse is born and perpetuated through sexual transgression down the ages. Bertrand’s own bestial urges expresses itself sexually as well as violently, and the only cure for his affliction appears to be a demented sort of true love. Though certainly not pornographic or particularly explicit, the sexuality is disturbing enough that I recommend parents read he book before their teenagers. I would only allow older, mature teens to read it myself.

For gamemasters the novel is most fruitful as a background template, demonstrating how to design a memorable non-player character. Bertrand makes an excellent tragic villain, and presenting the players with this sort of challenge, a monster that perhaps should not be killed yet must be stopped, is an excellent change of pace. Players may find less of immediate use, although Aymar’s investigations once he is in Paris itself may be instructive for Call of Cthulhu or other games involving supernatural investigations.

Despite its popularity, Endore’s novel was not filmed itself until 1962 when the famous British horror studio, Hammer Films, made Curse of the Werewolf. The novel’s psychological depth and overt sexuality was a deterrent to earlier dramatization. The filmed version moved the action to 18th century Spain, and was Oliver Reed's first starring role.

Bertrand’s rich, evocative prose makes the novel an engaging read despite the heavy subject matter. Readers looking for a classic horror story with depth and resonance will be well rewarded his work. Read it late on a windy night with a window open and dogs howling in the distance… and don’t be surprised if you crave red meat and more the next day…

All views in this blog are my own and represent the views of no other person, organization, or institution.

.jpg)