|

| The Nations at War: A Current History by Willis John Abbot (New York, Leslie-Judge Co., 1917) |

I've remained fascinated with this work for decades, because it was the closest thing to a 'primary source' that 7 year old me had yet seen. Abbot published a revised edition of the work in 1914 (maybe a typo in the catalog?), 1915, 1916, 1917, and 1918, providing a glimpse of the war through American eyes. The change in tone as the United States shifted from somewhat disinterested observer to eventual combatant was obvious throughout. So, I've decided to 'blog' the book, go through it chapter by chapter and share some of the images and passages that really impacted me as a child, or that I find particularly interesting from a historical or cultural standpoint today.

The book itself is readily available for purchase at many used book sites, and you can also find lots of pdfs on line. I use this pdf of the 1917 edition, which matches the edition I grew up with and which I still have (though I did have it rebound). I found it through the Open Library catalog entry on the Internet Archive site.

So, right off the bat, the cover is striking! It really emphasizes that this war felt like a continuation of the 19th century to those observing it, not the opening salvo of the 20th century. It was a real mystery to me as a kid, because I could only identify a few of the obvious states indicated, Germany, Japan, Great Britain, ect. Most of the nations used flags that I just was not familiar with. I can do a little better now.

The design shows the four Central Powers at the bottom, and the Allied Powers along the sides and the top. The Central Powers are arranged in a circle in the center bottom of the design, starting clockwise from the top: Imperial Germany, Bulgaria, The Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. The Allied Powers were more difficult, also going clockwise, starting from the bottom left, we have Montenegro, Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Serbia. an eclectic set of choices, since several Allied Powers, like Greece, were left out. The United States entered the war years after they had designed the covered, of course. :)

|

| One of the few color images in the book, a striking, and picturesque photograph. Page 29. |

The first chapter covers the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, as well as the diplomacy leading up to the war and the relative strengths of the combatants. There is a distinct anti-German bias throughout the book, "The assassination, Austro-Hungary's offended sovereignty, were but pretexts for the which the ruling powers of Germany were determined to force."

Vividly highlighting the anti-German bias of the book, on pages 16-17 Abbot claims that "Almost had the German Emperor paralleled in this twentieth century the situation created nearly two hundred years earlier by his famous progenitor Frederick the Great" and goes on to repeat a famous passage on Frederick:

"On the head of Frederic is all the blood which was shed in a war which raged during many years and in every quarter of the globe, the blood of the column of Fontenoy, the blood of the mountaineers who were slaughtered at Culloden. The evils produced by his wickedness were felt in lands where the name of Prussia was unknown; and, in order that he might rob a neighbour whom he had promised to defend, black men fought on the coast of Coromandel, and red men scalped each other by the Great Lakes of North America." (from Thomas B. Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays, Volume 2)

|

A pair of maps illustrating Abbot's argument that German and Russian ambitions were in direct competition. pp

8-9

|

|

| This photo is one of the reasons I wanted to join the Boy Scouts as a kid. p18. |

|

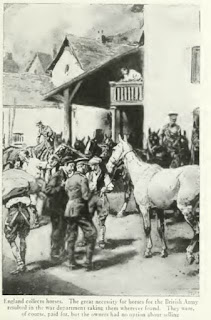

| I always felt sorry for the horses. p19 |

Other images really captured my imagination or helped

me get a handle on some of the less glamourous aspects of warfare. One image, showing British officers drafting horses for the war effort, stuck in my head and always popped to mind as I began to study military history, and thus logistics, seriously in graduate school. So did many images of trains and marshaling yards in the books, and its description of the complicated process of mobilizing mass armies for warfare. The first images highlighting the horrors of war appeared in the first chapter as well. Not yet photographs, but shocking drawings nonetheless.

|

| I felt even more sorry for the horses after looking at this page. p 23. |

|

| I believe that is supposed to be a Taube. p24. |

|

| It had a diagram! p25 |

Other images grabbed my technical imagination. The Lewis Gun looked like something straight out of Jules Verne, but it was a real, functioning weapon. The aircraft depicted in this work were even more fantastic looking, even in this first chapter, whether they were the target of a Lewis Gun or just a tail peaking out of a truck transport.

|

| Pure imagination fuel! p25. |

But this last image really highlighted, for me, the oddness of 1914, and so i close out this first Blogging the Nations at War entry with it. The Belgian infantry and their formation simply look like they are straight out of another time, and not really ready, brave as they might be, to face the storm of steel and fire that the 20th century is sending their way.

|

| Top hats and bayonet swords... my son is trying to get into historical reenacting. I kind of want to do an impression of Belgian infantry 1914. There cannot be many who reenact them! p19 |

All views in this blog are my own and represent the views of no other person, organization, or institution.